Free MCAT practice exam

Unlike adult cardiomyocytes, which lack the ability to regenerate after heart injury, neonatal mammals can significantly regenerate cardiomyocytes following cardiac damage. However, this regenerative capacity begins to decline shortly after birth, typically by postnatal day 7, when cardiomyocytes enter cell-cycle arrest and changes in blood circulation occur.

In an effort to understand the causes of this cell-cycle arrest, researchers observed that in mice, there is a marked increase in mitochondrial DNA activity immediately after birth. This indicates a shift from anaerobic glycolysis to the oxygen-dependent mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (MOP) pathway. During this shift, an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) was also noted. To further investigate the connection between oxygen levels, ROS, and cardiomyocyte growth and division, the researchers conducted three additional experiments.

Experiment 1

In this experiment, neonatal mice were exposed to either hyperoxic or mildly hypoxic environments to evaluate the effect of oxygen levels on cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest. The results revealed a notable reduction in cardiomyocyte cell size following hypoxia exposure, while hyperoxia had no impact on cell size. The presence of phosphorylated histone H3 Ser 10, a marker for G2-M phase progression, was significantly reduced in the hyperoxic group and increased in the hypoxic group. Furthermore, Aurora B kinase localization at the cleavage furrow, a marker of cytokinesis, was lower in the hyperoxic group and slightly higher in the hypoxic group.

Experiment 2

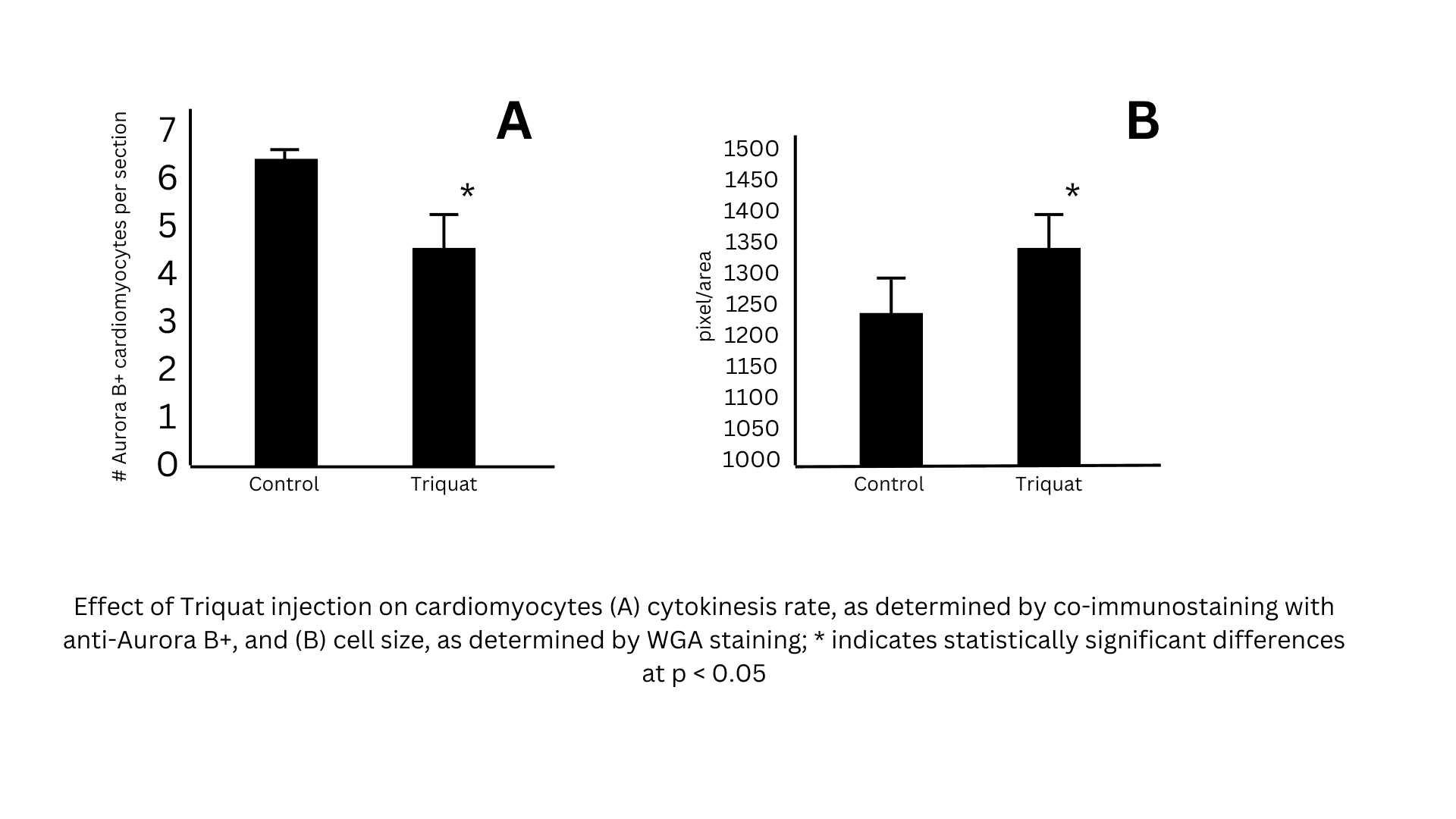

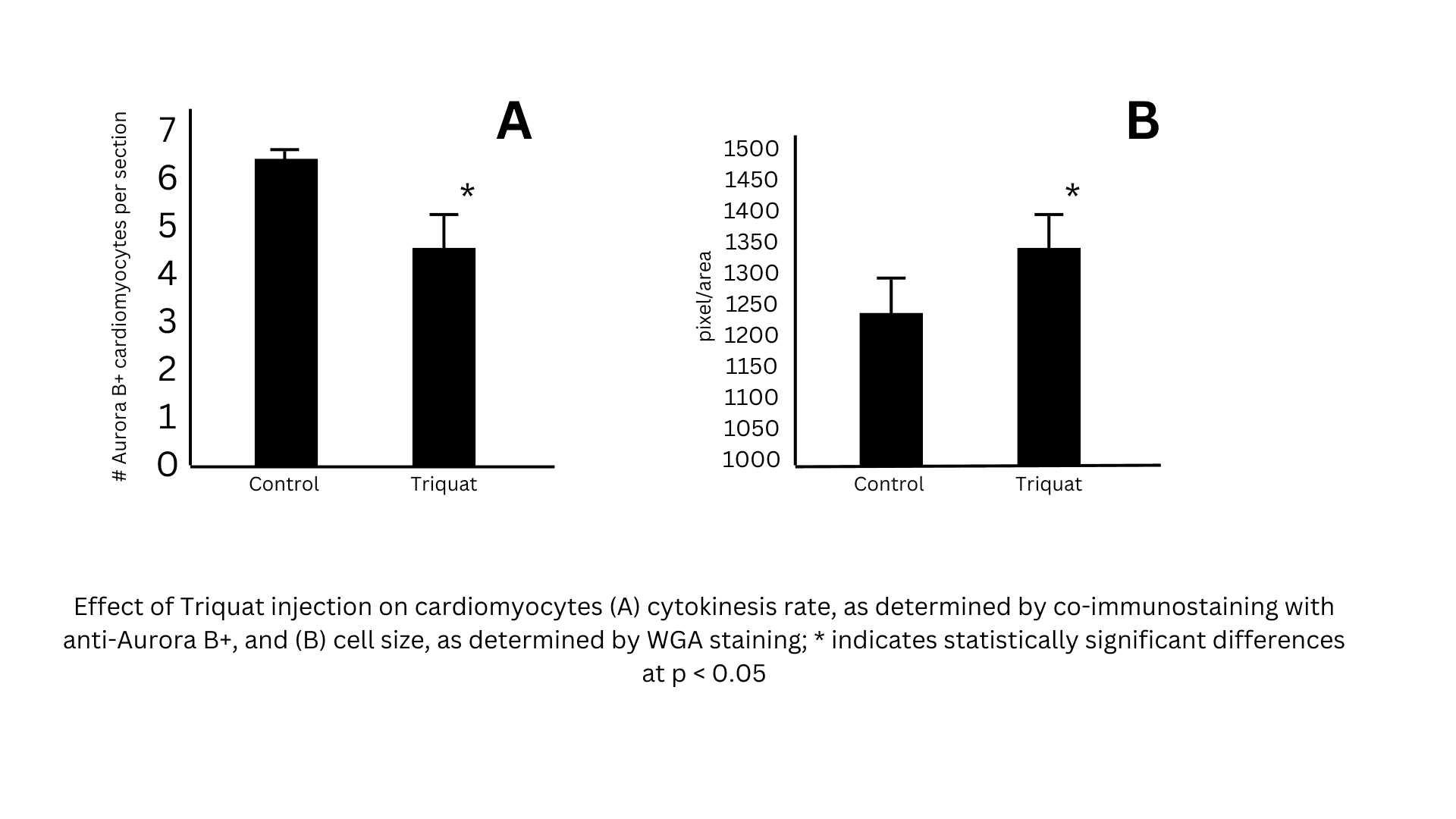

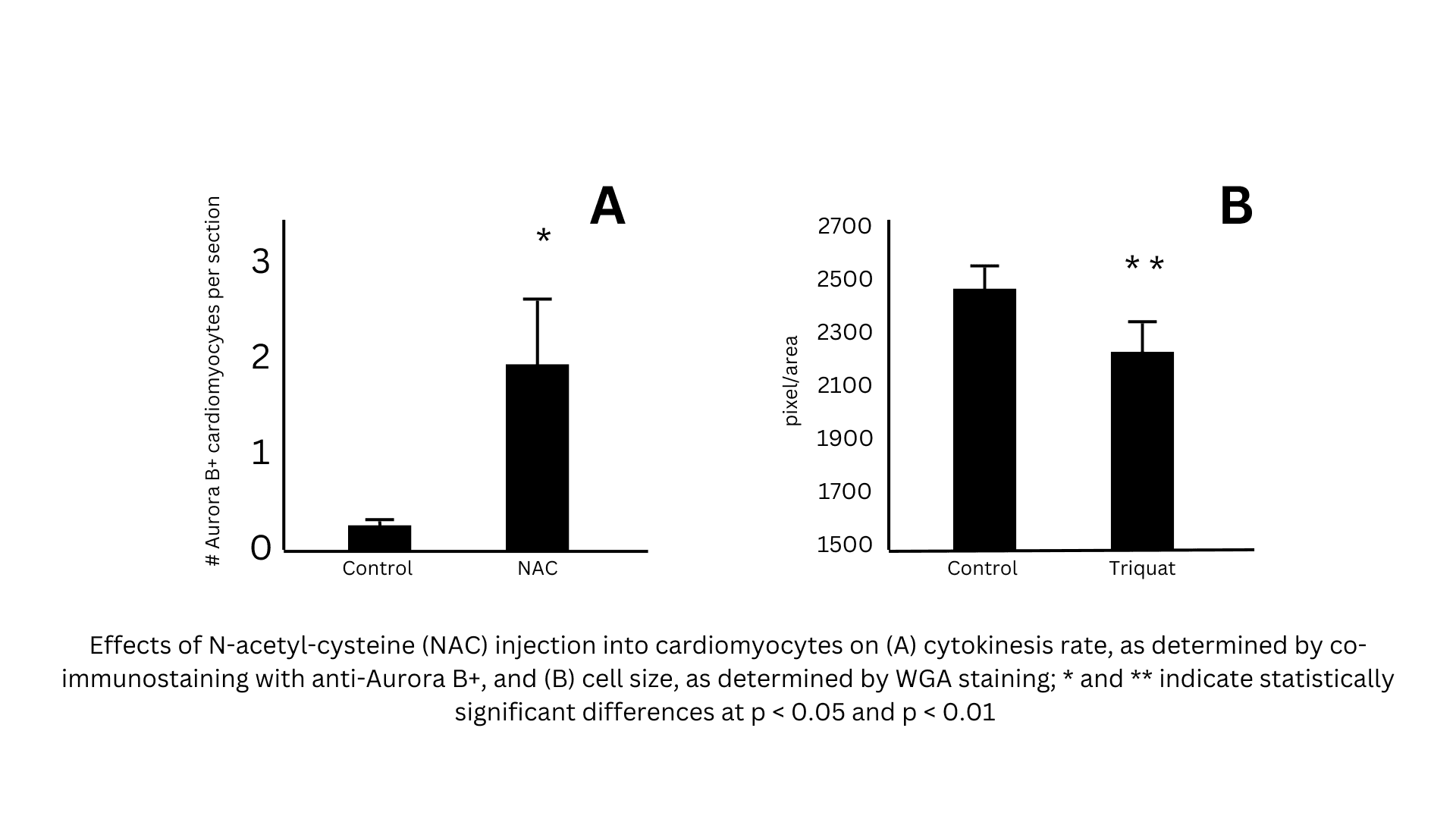

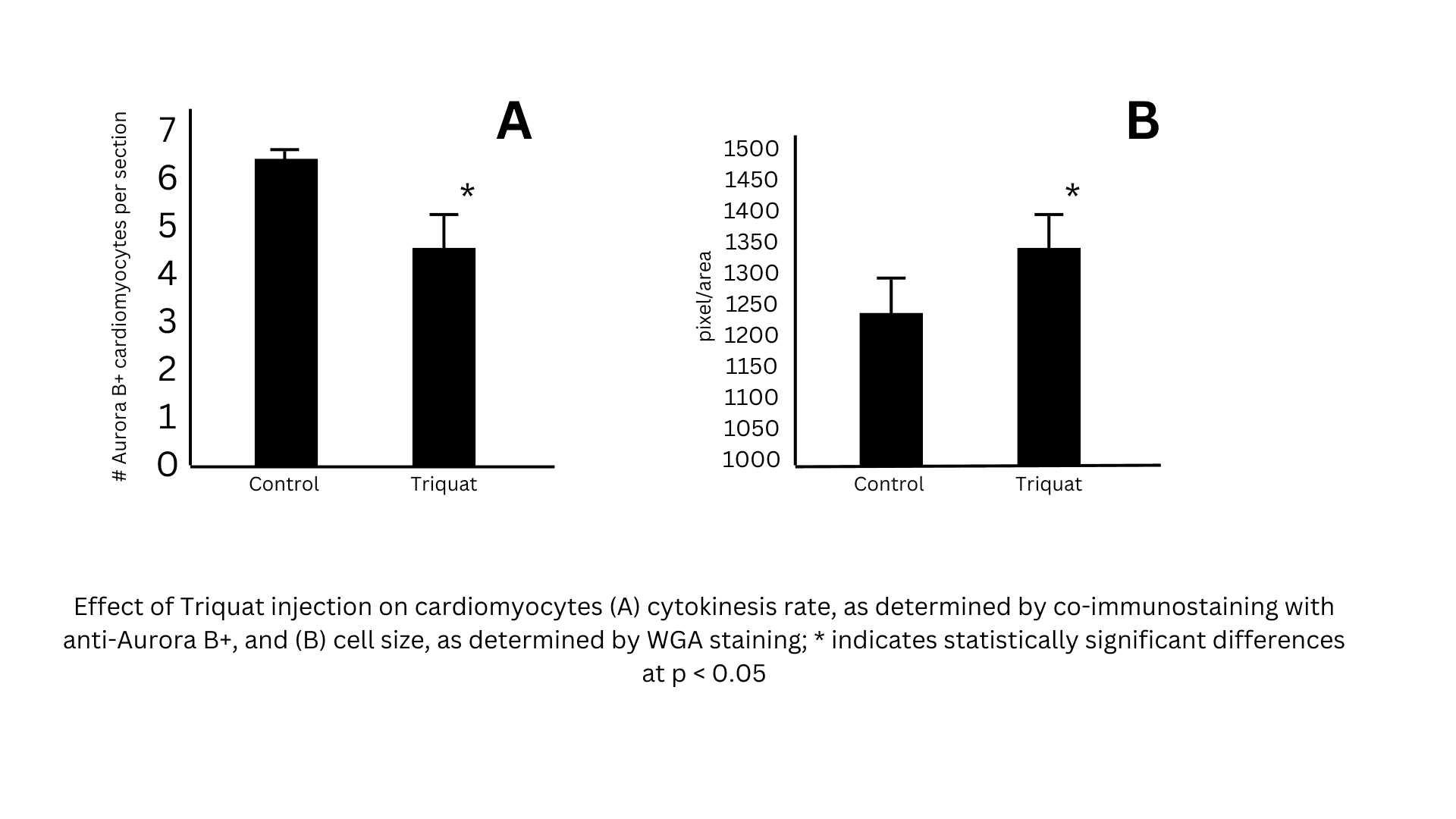

Mice were administered Triquat, a compound known to increase ROS production. The rate of cardiomyocyte cytokinesis and cell size were then measured using Aurora B localization and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining. The results demonstrated significant changes in these metrics following Triquat injection, with statistical differences observed at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Experiment 3

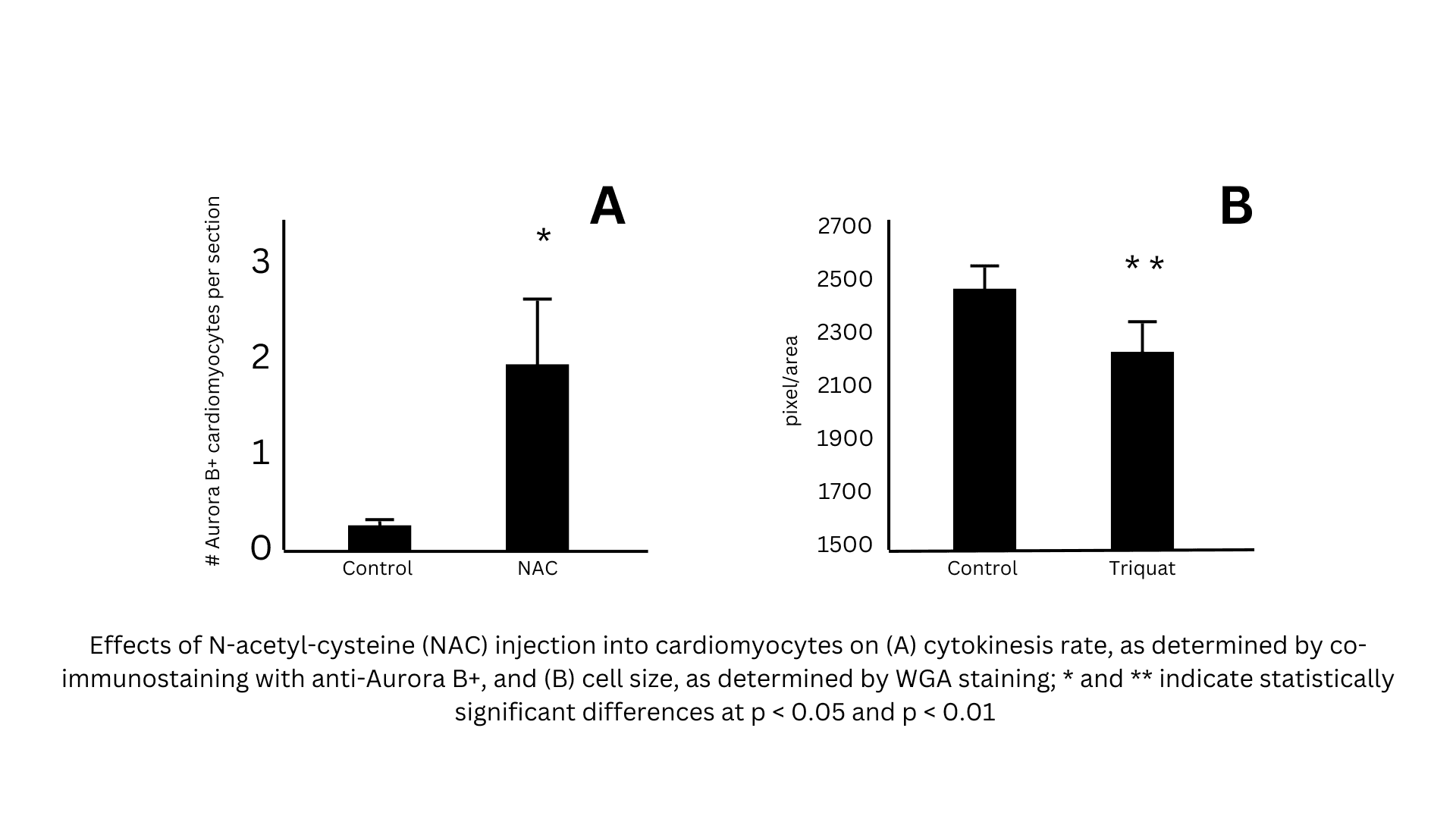

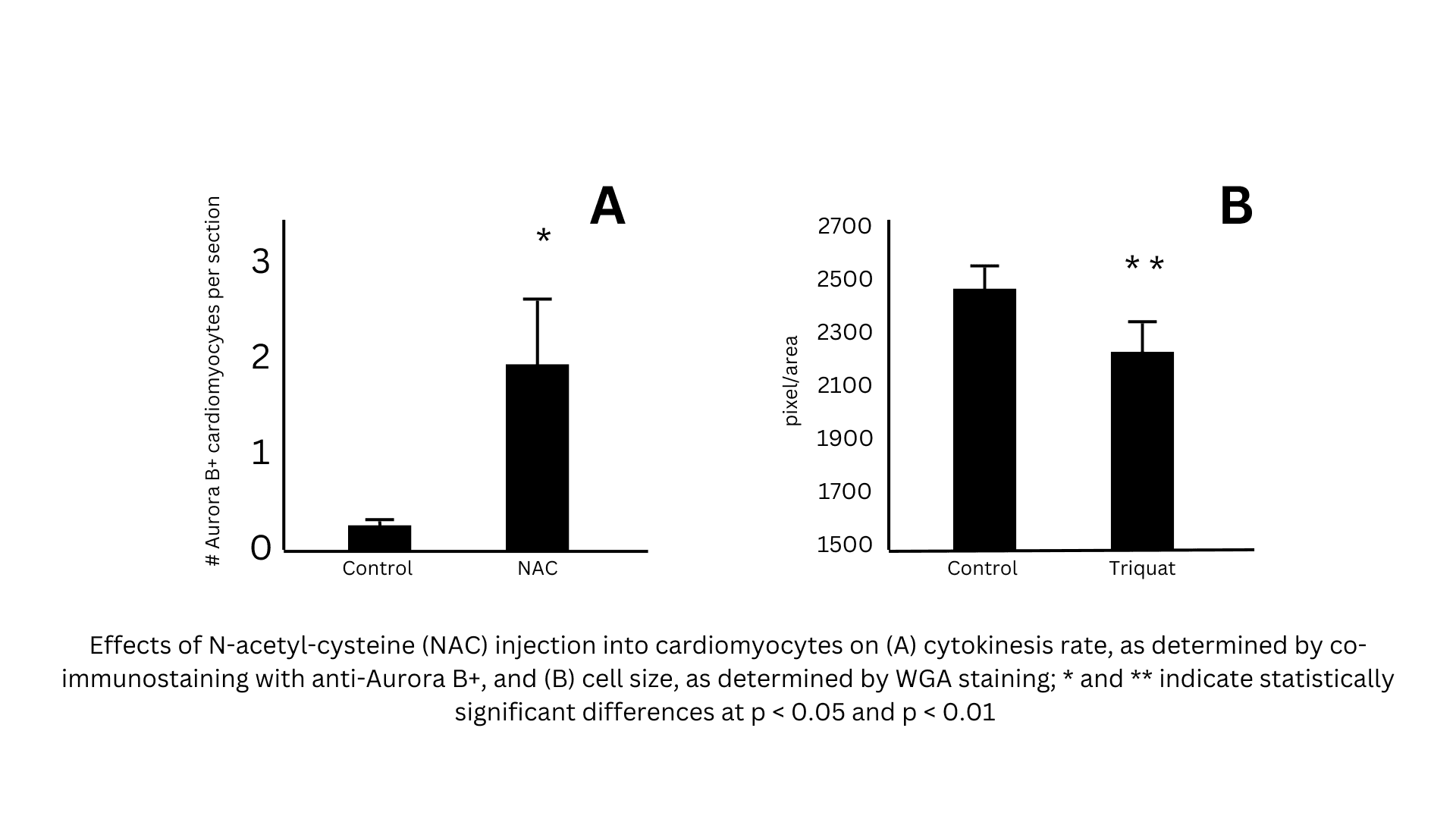

In the final experiment, mice were injected with N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), a molecule that neutralizes ROS. The researchers assessed cardiomyocyte cytokinesis and cell size again, with the findings presented in the figure below These results highlighted the effects of NAC treatment, with statistically significant differences noted at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Overall, these experiments shed light on how oxygen conditions and ROS levels influence cardiomyocyte behavior during postnatal development.

How do cytokinesis or apoptosis rates relate to cardiomyocyte cell cycle arrest?

Unlike adult cardiomyocytes, which lack the ability to regenerate after heart injury, neonatal mammals can significantly regenerate cardiomyocytes following cardiac damage. However, this regenerative capacity begins to decline shortly after birth, typically by postnatal day 7, when cardiomyocytes enter cell-cycle arrest and changes in blood circulation occur.

In an effort to understand the causes of this cell-cycle arrest, researchers observed that in mice, there is a marked increase in mitochondrial DNA activity immediately after birth. This indicates a shift from anaerobic glycolysis to the oxygen-dependent mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (MOP) pathway. During this shift, an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) was also noted. To further investigate the connection between oxygen levels, ROS, and cardiomyocyte growth and division, the researchers conducted three additional experiments.

Experiment 1

In this experiment, neonatal mice were exposed to either hyperoxic or mildly hypoxic environments to evaluate the effect of oxygen levels on cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest. The results revealed a notable reduction in cardiomyocyte cell size following hypoxia exposure, while hyperoxia had no impact on cell size. The presence of phosphorylated histone H3 Ser 10, a marker for G2-M phase progression, was significantly reduced in the hyperoxic group and increased in the hypoxic group. Furthermore, Aurora B kinase localization at the cleavage furrow, a marker of cytokinesis, was lower in the hyperoxic group and slightly higher in the hypoxic group.

Experiment 2

Mice were administered Triquat, a compound known to increase ROS production. The rate of cardiomyocyte cytokinesis and cell size were then measured using Aurora B localization and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining. The results demonstrated significant changes in these metrics following Triquat injection, with statistical differences observed at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Experiment 3

In the final experiment, mice were injected with N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), a molecule that neutralizes ROS. The researchers assessed cardiomyocyte cytokinesis and cell size again, with the findings presented in the figure below These results highlighted the effects of NAC treatment, with statistically significant differences noted at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Overall, these experiments shed light on how oxygen conditions and ROS levels influence cardiomyocyte behavior during postnatal development.

What conclusion is most supported by results of Experiment 1?

Unlike adult cardiomyocytes, which lack the ability to regenerate after heart injury, neonatal mammals can significantly regenerate cardiomyocytes following cardiac damage. However, this regenerative capacity begins to decline shortly after birth, typically by postnatal day 7, when cardiomyocytes enter cell-cycle arrest and changes in blood circulation occur.

In an effort to understand the causes of this cell-cycle arrest, researchers observed that in mice, there is a marked increase in mitochondrial DNA activity immediately after birth. This indicates a shift from anaerobic glycolysis to the oxygen-dependent mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (MOP) pathway. During this shift, an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) was also noted. To further investigate the connection between oxygen levels, ROS, and cardiomyocyte growth and division, the researchers conducted three additional experiments.

Experiment 1

In this experiment, neonatal mice were exposed to either hyperoxic or mildly hypoxic environments to evaluate the effect of oxygen levels on cardiomyocyte cell-cycle arrest. The results revealed a notable reduction in cardiomyocyte cell size following hypoxia exposure, while hyperoxia had no impact on cell size. The presence of phosphorylated histone H3 Ser 10, a marker for G2-M phase progression, was significantly reduced in the hyperoxic group and increased in the hypoxic group. Furthermore, Aurora B kinase localization at the cleavage furrow, a marker of cytokinesis, was lower in the hyperoxic group and slightly higher in the hypoxic group.

Experiment 2

Mice were administered Triquat, a compound known to increase ROS production. The rate of cardiomyocyte cytokinesis and cell size were then measured using Aurora B localization and wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) staining. The results demonstrated significant changes in these metrics following Triquat injection, with statistical differences observed at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Experiment 3

In the final experiment, mice were injected with N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC), a molecule that neutralizes ROS. The researchers assessed cardiomyocyte cytokinesis and cell size again, with the findings presented in the figure below These results highlighted the effects of NAC treatment, with statistically significant differences noted at p < 0.05 and p < 0.01.

Overall, these experiments shed light on how oxygen conditions and ROS levels influence cardiomyocyte behavior during postnatal development.

Which condition(s) would prenatal or postnatal (pregnancy periods) exposure to Triquat most likely pose an increased risk according to the passage?

- Small cardiomyocyte size

- Premature cell-cycle arrest

- Excess cell proliferation

A cardiac monitor assesses the proper functioning of a patient's heart by detecting its electrical activity. Electrodes attached to the patient's skin capture these electrical signals and transmit them to the central monitor, where the data is displayed.

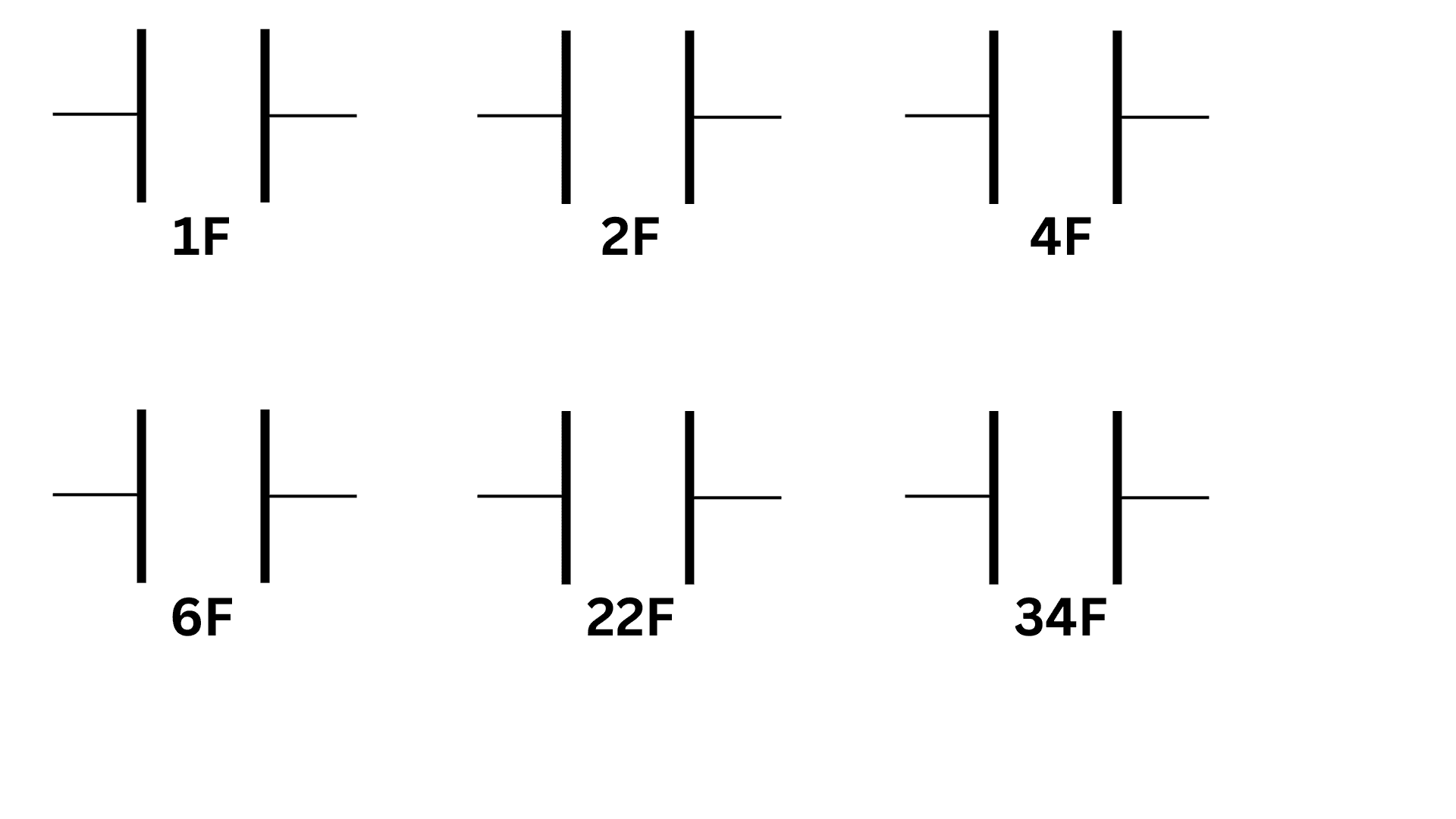

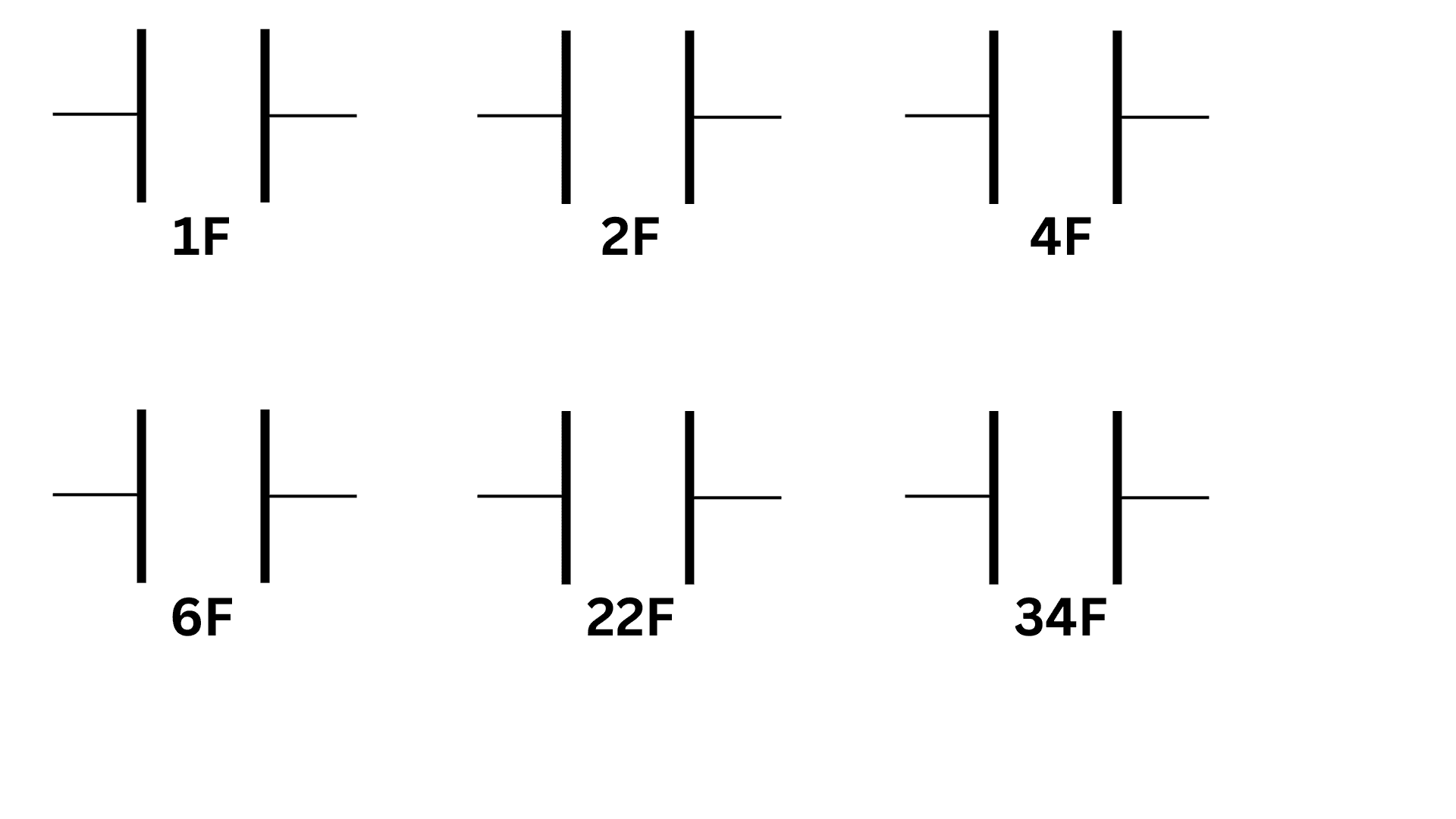

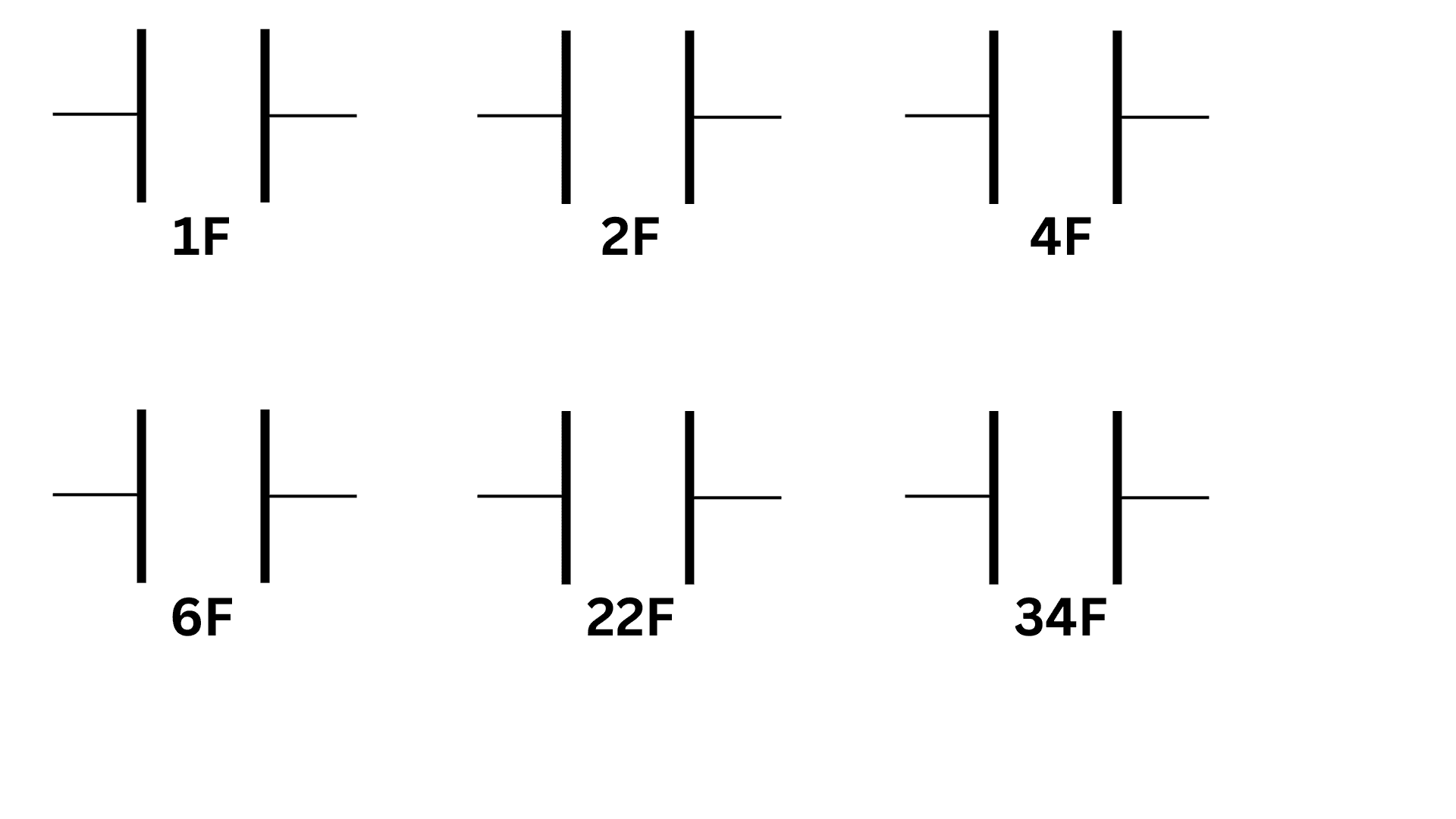

At a hospital, a technician is working with similar devices, known as electrocardiography (ECG) monitors. The hospital's ECG machines rely on a single 13F capacitor to operate. When in use, this capacitor experiences a voltage of 2V.

During the morning, the monitor functioned without an issue, however later in the day, one of the ECG monitors malfunctions due to the failure of its 13F capacitor. Upon inspecting the hospital's supply, the tech discovers that there are no spare 13F capacitors in stock. Instead, the storage contains a selection of different capacitors. The tech begins to explore alternative configurations to restore the ECG functionality.

Of the available capacitors, which could you connect in parallel to replace one of the malfunctioning capacitors?

A cardiac monitor assesses the proper functioning of a patient's heart by detecting its electrical activity. Electrodes attached to the patient's skin capture these electrical signals and transmit them to the central monitor, where the data is displayed.

At a hospital, a technician is working with similar devices, known as electrocardiography (ECG) monitors. The hospital's ECG machines rely on a single 13F capacitor to operate. When in use, this capacitor experiences a voltage of 2V.

During the morning, the monitor functioned without an issue, however later in the day, one of the ECG monitors malfunctions due to the failure of its 13F capacitor. Upon inspecting the hospital's supply, the tech discovers that there are no spare 13F capacitors in stock. Instead, the storage contains a selection of different capacitors. The tech begins to explore alternative configurations to restore the ECG functionality.

Of the available capacitors, which could you connect in series to replace one of the malfunctioning capacitors?

A cardiac monitor assesses the proper functioning of a patient's heart by detecting its electrical activity. Electrodes attached to the patient's skin capture these electrical signals and transmit them to the central monitor, where the data is displayed.

At a hospital, a technician is working with similar devices, known as electrocardiography (ECG) monitors. The hospital's ECG machines rely on a single 13F capacitor to operate. When in use, this capacitor experiences a voltage of 2V.

During the morning, the monitor functioned without an issue, however later in the day, one of the ECG monitors malfunctions due to the failure of its 13F capacitor. Upon inspecting the hospital's supply, the tech discovers that there are no spare 13F capacitors in stock. Instead, the storage contains a selection of different capacitors. The tech begins to explore alternative configurations to restore the ECG functionality.

In the properly functioning monitoring equipment, what is the energy stored by a 13F capacitor?

THE GOTHIC PALACES OF VENICE

The location of Venice upon a group of islands, sufficiently removed from the mainland to make it impossible to effectually attack it from this side, and naturally defended on the side towards the sea by a long chain of low islands, separated by shallow inlets and winding channels, making it difficult to approach, has rendered the city peculiarly free from the disturbing influences which were constantly at work in the neighboring cities of Italy during the Middle Ages.

While her neighbors were building strong encircling walls, each individual house a fortress in itself, Venice rested secure in her natural defences and built her palaces open down to the water's edge, with no attempt at fortification. Her hardy and adventurous inhabitants rapidly extended their trade to all quarters of the world and accumulated vast wealth, which was freely lavished on public and private buildings. The magnificence of the former was only equaled in the days of ancient Rome, and it is doubtful if the latter have ever been surpassed in sumptuousness and splendor.

The palaces of Venice form an architectural group of great interest, in many respects quite distinct from the contemporary buildings on the mainland. They were carefully planned to satisfy the demands for comfort and convenience as well as display. Most of them have the same arrangement of plan, and were commonly built of two lofty and two low stories. On the ground floor, or water level, is a hall running back from the gate to a bit of garden at the other side of the palace, and on either side of this hall, which was hung with the family trophies of the chase and war, are the porter's lodge and gondoliers' rooms. On the first and second stories are the family apartments, opening on either side from great halls, of the same extent as that below, but with loftier roofs, of heavy rafters gilded or painted. The fourth floor is of the same arrangement, but has a lower roof, and was devoted to the better class of servants. Of the two stories used by the family, the third is the loftier and airier, and was occupied in summer; the second was the winter apartment. On either hand the rooms open in suites. The courtyard at the rear usually had a well in its centre with an ornamental curb; and access to the upper floors of the house was gained by an exterior staircase in the court, which was often elaborately enriched with carved ornament.

The materials used in construction are mostly red and white marbles, used with a fine color sense, and the desire for abundance of color was frequently further gratified by painting the exterior walls with elaborate pictorial decorations. The earliest palaces are Byzantine, but with the growth of the Gothic movement these were gradually superseded, although the Gothic influence worked more slowly here than on the mainland. The richest and most elaborate work was built at this period. Finally the Renaissance took the place of Gothic; and the later palaces, built in this style, show strongly the debased condition into which the art of Venice fell in the Dark Ages.

Which of the following can be inferred about Venice during the Middle Ages based on information in the passage?

THE GOTHIC PALACES OF VENICE

The location of Venice upon a group of islands, sufficiently removed from the mainland to make it impossible to effectually attack it from this side, and naturally defended on the side towards the sea by a long chain of low islands, separated by shallow inlets and winding channels, making it difficult to approach, has rendered the city peculiarly free from the disturbing influences which were constantly at work in the neighboring cities of Italy during the Middle Ages.

While her neighbors were building strong encircling walls, each individual house a fortress in itself, Venice rested secure in her natural defences and built her palaces open down to the water's edge, with no attempt at fortification. Her hardy and adventurous inhabitants rapidly extended their trade to all quarters of the world and accumulated vast wealth, which was freely lavished on public and private buildings. The magnificence of the former was only equaled in the days of ancient Rome, and it is doubtful if the latter have ever been surpassed in sumptuousness and splendor.

The palaces of Venice form an architectural group of great interest, in many respects quite distinct from the contemporary buildings on the mainland. They were carefully planned to satisfy the demands for comfort and convenience as well as display. Most of them have the same arrangement of plan, and were commonly built of two lofty and two low stories. On the ground floor, or water level, is a hall running back from the gate to a bit of garden at the other side of the palace, and on either side of this hall, which was hung with the family trophies of the chase and war, are the porter's lodge and gondoliers' rooms. On the first and second stories are the family apartments, opening on either side from great halls, of the same extent as that below, but with loftier roofs, of heavy rafters gilded or painted. The fourth floor is of the same arrangement, but has a lower roof, and was devoted to the better class of servants. Of the two stories used by the family, the third is the loftier and airier, and was occupied in summer; the second was the winter apartment. On either hand the rooms open in suites. The courtyard at the rear usually had a well in its centre with an ornamental curb; and access to the upper floors of the house was gained by an exterior staircase in the court, which was often elaborately enriched with carved ornament.

The materials used in construction are mostly red and white marbles, used with a fine color sense, and the desire for abundance of color was frequently further gratified by painting the exterior walls with elaborate pictorial decorations. The earliest palaces are Byzantine, but with the growth of the Gothic movement these were gradually superseded, although the Gothic influence worked more slowly here than on the mainland. The richest and most elaborate work was built at this period. Finally the Renaissance took the place of Gothic; and the later palaces, built in this style, show strongly the debased condition into which the art of Venice fell in the Dark Ages.

What can we assume about the houses of mainland Italian cities?

THE GOTHIC PALACES OF VENICE

The location of Venice upon a group of islands, sufficiently removed from the mainland to make it impossible to effectually attack it from this side, and naturally defended on the side towards the sea by a long chain of low islands, separated by shallow inlets and winding channels, making it difficult to approach, has rendered the city peculiarly free from the disturbing influences which were constantly at work in the neighboring cities of Italy during the Middle Ages.

While her neighbors were building strong encircling walls, each individual house a fortress in itself, Venice rested secure in her natural defences and built her palaces open down to the water's edge, with no attempt at fortification. Her hardy and adventurous inhabitants rapidly extended their trade to all quarters of the world and accumulated vast wealth, which was freely lavished on public and private buildings. The magnificence of the former was only equaled in the days of ancient Rome, and it is doubtful if the latter have ever been surpassed in sumptuousness and splendor.

The palaces of Venice form an architectural group of great interest, in many respects quite distinct from the contemporary buildings on the mainland. They were carefully planned to satisfy the demands for comfort and convenience as well as display. Most of them have the same arrangement of plan, and were commonly built of two lofty and two low stories. On the ground floor, or water level, is a hall running back from the gate to a bit of garden at the other side of the palace, and on either side of this hall, which was hung with the family trophies of the chase and war, are the porter's lodge and gondoliers' rooms. On the first and second stories are the family apartments, opening on either side from great halls, of the same extent as that below, but with loftier roofs, of heavy rafters gilded or painted. The fourth floor is of the same arrangement, but has a lower roof, and was devoted to the better class of servants. Of the two stories used by the family, the third is the loftier and airier, and was occupied in summer; the second was the winter apartment. On either hand the rooms open in suites. The courtyard at the rear usually had a well in its centre with an ornamental curb; and access to the upper floors of the house was gained by an exterior staircase in the court, which was often elaborately enriched with carved ornament.

The materials used in construction are mostly red and white marbles, used with a fine color sense, and the desire for abundance of color was frequently further gratified by painting the exterior walls with elaborate pictorial decorations. The earliest palaces are Byzantine, but with the growth of the Gothic movement these were gradually superseded, although the Gothic influence worked more slowly here than on the mainland. The richest and most elaborate work was built at this period. Finally the Renaissance took the place of Gothic; and the later palaces, built in this style, show strongly the debased condition into which the art of Venice fell in the Dark Ages.

The author would most likely agree with which of the following statements, based on information provided in the passage:

Empirical political science

In contrast to normative political science, which asks how political life ought to be ordered, empirical political science investigates how politics actually functions. Its central objectives are description, explanation, and—where possible—prediction, isolating recurrent patterns from singular anomalies.

The empirical approach presupposes an external realm of verifiable fact. Questions are therefore deemed empirical if they can be adjudicated by systematic evidence. The tally of ballots cast for a candidate exemplifies such a question: although methodological complications may generate slight discrepancies across counting procedures, a determinate total nonetheless exists. Factual claims, of course, can be contested. In certain domains, i.e., the existence of extraterrestrial life, data remain fragmentary or disputed. Competing scholars may present inconclusive or contested evidence, and at most one position can ultimately prove correct; definitive corroboration is simply not yet at hand.

Disagreement thus sometimes stems from genuine evidentiary ambiguity. Frequently, however, resistance to empirically grounded conclusions reflects motivated reasoning: individuals first adopt a preferred stance—"gun regulation enhances public safety" or "gun regulation puts public safety at risk"—and subsequently cherry-pick supportive information while discounting contrary findings. In still other situations, actors recognize the facts but suppress or distort them for material gain. The tobacco industry's long-standing denial of nicotine's addictive and pathological properties, despite overwhelming scientific consensus, illustrates such strategic obfuscation.

Suppose available data show that citizens with higher educational attainment or greater income exhibit higher turnout rates. An empirical political scientist records the correlation, advances a causal account, perhaps that socio-economically advantaged individuals are more likely to believe they have political efficacy, and derives the probabilistic forecast that they will vote more frequently than their less-advantaged counterparts. The investigator does not pronounce whether this disparity is normatively desirable; evaluating the justice or injustice of unequal participation belongs to normative theory.

Indeed, empirical findings alone cannot resolve prescriptive questions. Discovering that one segment of the electorate votes at elevated levels says nothing about whether it ought to wield proportional influence, nor whether public policy should privilege its preferences over those of less active groups. Moral judgment requires an additional, explicitly normative argument beyond the reach of empirical description and prediction.

Which methodological step would most strengthen an empirical political scientist's causal claim that perceived efficacy drives voter turnout among the well-educated?

Empirical political science

In contrast to normative political science, which asks how political life ought to be ordered, empirical political science investigates how politics actually functions. Its central objectives are description, explanation, and—where possible—prediction, isolating recurrent patterns from singular anomalies.

The empirical approach presupposes an external realm of verifiable fact. Questions are therefore deemed empirical if they can be adjudicated by systematic evidence. The tally of ballots cast for a candidate exemplifies such a question: although methodological complications may generate slight discrepancies across counting procedures, a determinate total nonetheless exists. Factual claims, of course, can be contested. In certain domains, i.e., the existence of extraterrestrial life, data remain fragmentary or disputed. Competing scholars may present inconclusive or contested evidence, and at most one position can ultimately prove correct; definitive corroboration is simply not yet at hand.

Disagreement thus sometimes stems from genuine evidentiary ambiguity. Frequently, however, resistance to empirically grounded conclusions reflects motivated reasoning: individuals first adopt a preferred stance—"gun regulation enhances public safety" or "gun regulation puts public safety at risk"—and subsequently cherry-pick supportive information while discounting contrary findings. In still other situations, actors recognize the facts but suppress or distort them for material gain. The tobacco industry's long-standing denial of nicotine's addictive and pathological properties, despite overwhelming scientific consensus, illustrates such strategic obfuscation.

Suppose available data show that citizens with higher educational attainment or greater income exhibit higher turnout rates. An empirical political scientist records the correlation, advances a causal account, perhaps that socio-economically advantaged individuals are more likely to believe they have political efficacy, and derives the probabilistic forecast that they will vote more frequently than their less-advantaged counterparts. The investigator does not pronounce whether this disparity is normatively desirable; evaluating the justice or injustice of unequal participation belongs to normative theory.

Indeed, empirical findings alone cannot resolve prescriptive questions. Discovering that one segment of the electorate votes at elevated levels says nothing about whether it ought to wield proportional influence, nor whether public policy should privilege its preferences over those of less active groups. Moral judgment requires an additional, explicitly normative argument beyond the reach of empirical description and prediction.

A drug maker who is aware of but hides a risk associated with use of their product serves to illustrate which concept?

Empirical political science

In contrast to normative political science, which asks how political life ought to be ordered, empirical political science investigates how politics actually functions. Its central objectives are description, explanation, and—where possible—prediction, isolating recurrent patterns from singular anomalies.

The empirical approach presupposes an external realm of verifiable fact. Questions are therefore deemed empirical if they can be adjudicated by systematic evidence. The tally of ballots cast for a candidate exemplifies such a question: although methodological complications may generate slight discrepancies across counting procedures, a determinate total nonetheless exists. Factual claims, of course, can be contested. In certain domains, i.e., the existence of extraterrestrial life, data remain fragmentary or disputed. Competing scholars may present inconclusive or contested evidence, and at most one position can ultimately prove correct; definitive corroboration is simply not yet at hand.

Disagreement thus sometimes stems from genuine evidentiary ambiguity. Frequently, however, resistance to empirically grounded conclusions reflects motivated reasoning: individuals first adopt a preferred stance—"gun regulation enhances public safety" or "gun regulation puts public safety at risk"—and subsequently cherry-pick supportive information while discounting contrary findings. In still other situations, actors recognize the facts but suppress or distort them for material gain. The tobacco industry's long-standing denial of nicotine's addictive and pathological properties, despite overwhelming scientific consensus, illustrates such strategic obfuscation.

Suppose available data show that citizens with higher educational attainment or greater income exhibit higher turnout rates. An empirical political scientist records the correlation, advances a causal account, perhaps that socio-economically advantaged individuals are more likely to believe they have political efficacy, and derives the probabilistic forecast that they will vote more frequently than their less-advantaged counterparts. The investigator does not pronounce whether this disparity is normatively desirable; evaluating the justice or injustice of unequal participation belongs to normative theory.

Indeed, empirical findings alone cannot resolve prescriptive questions. Discovering that one segment of the electorate votes at elevated levels says nothing about whether it ought to wield proportional influence, nor whether public policy should privilege its preferences over those of less active groups. Moral judgment requires an additional, explicitly normative argument beyond the reach of empirical description and prediction.

If two scholars amass conflicting but inconclusive evidence about extraterrestrial life, their dispute exemplifies which limitation of empiricism?